ReSTIR GSGI - Fast Ray Traced GI with Virtual Lights

Today I’m going to talk about a ray traced global illumination technique which I’m calling ReSTIR Geometry Sampling Global Illumination, or GSGI for short. It’s based around the ReSTIR direct lighting algorithm, and aims to achieve the following goals:

- Very high speed

- Diffuse (Lambertian) ray traced GI

- Infinite bounces

- No restrictions on geometry

- Capable of handling arbitrarily large scenes

- Can be tuned for very fast lighting response

- Good enough quality

The last point is obviously subjective. Our comparison will be ReSTIR GI, which extends ReSTIR’s resampling approach to global illumination. ReSTIR GI produces very high quality results, and can do so faster than previous solutions which offer similar quality, but still has a high performance cost for a real-time use case like a videogame.

ReSTIR GSGI uses a very different approach to ReSTIR GI, but I’ll be comparing it to ReSTIR GI in both performance and quality. The goal is to achieve around an order of magnitude faster performance, making it viable for real-time use on mid-range hardware, while still achieving quality which is subjectively good enough.

As we’ll see by the end of this article, my current implementation of GSGI is capable of running at a very high speed, and can produce good results in certain circumstances. However, it can struggle with more complex lighting scenarios, which could limit its usefulness, or require further work to address.

ReSTIR

First, we need a brief introduction to ReSTIR. A full description of how ReSTIR functions is well beyond the scope of this article, but there are some key concepts we’ll need to understand for context. I’ll include links below for anyone interested in learning more about it.

ReSTIR stands for Reservoir Spatio-Temporal Importance Resampling. It’s a direct lighting algorithm, and what makes it so appealing is that it can efficiently calculate lighting (and shadowing) for an extremely large number of light sources, into the millions. The algorithm itself is $O(0)$ with respect to the number of light sources, which is to say its performance is completely independent of the number of lights, but memory limits do come into play, as you have to actually store all those lights in GPU memory, and there are some pre-processing steps which scale with the number of lights. Still, the real-world performance impact of moving from a single-digit number of light sources to hundreds of thousands is very low.

A key part of the ReSTIR algorithm is resampling. Here it reuses information from neighbouring pixels (spatial resampling) and the same pixel in previous frames (temporal resampling) in order to significantly improve the sample quality for each pixel. How the spatial and temporal resampling interact with GSGI will be important later.

Geometry Sampling Global Illumination

The core concept of GSGI is to randomly sample points on the geometry in the scene, and then create virtual lights representing indirect illumination reflected off those points, which are then fed into the ReSTIR algorithm to calculate global illumination.

Using virtual lights to represent global illumination not a new concept, and has been used in the past in techniques such as Instant Global Illumination. Those previous approaches have usually been limited to a very low number of virtual lights, though, for performance reasons. With ReSTIR being able to handle a very large number of light sources with minimal performance impact, it’s now feasible to use hundreds of thousands, or even millions of virtual lights in a real-time environment.

This can achieve a very high level of performance because there isn’t a separate per-pixel GI pass. Virtual lights are fed into the same ReSTIR pass as is used for direct illumination, so both direct and indirect illumination are calculated as part of a single pass. The creation of virtual lights is independent of resolution, and good quality can be achieved with only around 16K new virtual lights per frame, so performance can be far better than techniques which require non-trivial per-pixel calculations.

The technique also allows for an effectively infinite number of light bounces, as the virtual lights from previous frames can be included in the light sources used to calculate the light reflected off new samples. Each sample represents a single bounce, but as samples feed into each other they can represent more complex lighting paths.

Radial Geometry Sampling

There are many potential approaches to sampling scene geometry. The one which I’ve settled on, which I’ll call radial sampling, was chosen as it generates a higher sample density close to the camera, and a lower density further away. Specifically, it produces a sample density proportional to $1/d^2$, which means the sample density is proportional the size of objects on screen. This is perfect for large scenes, such as in open world games, as we can represent relatively fine-grained GI on objects close to the camera, with coarse-grained GI further away, all exactly in proportion to the size they would be on screen. This bias can then be easily corrected when generating the virtual lights.

Radial geometry sampling leverages ray tracing hardware, and works by casting rays in random directions from the location of the camera. We use anyhit shaders, which are typically used for transparency calculations, as they trigger for every piece of geometry hit by the ray. This is beneficial to us, as we want to randomly sample one of those surfaces for each ray.

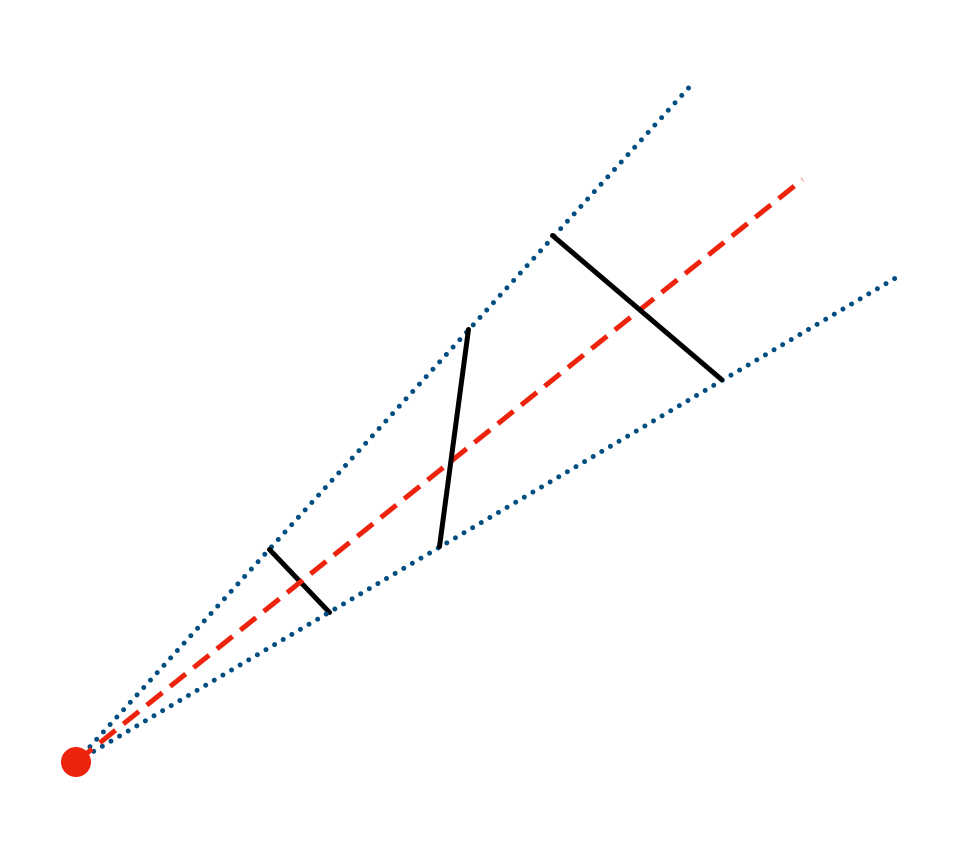

The above diagram illustrates the sampling approach in two dimensions. The grey dashed lines are rays traced in random directions from the location of the camera. Each surface hit by a ray is evaluated (the blue circles) and one is chosen for each ray (the filled blue circles).

To determine which surface to use, we use reservoir sampling. For each surface we hit, we calculate a weight $W$ based on the angle of the surface to the ray, and we accept this surface as our sample with a probability of $W/W_s$, where $W_s$ is the sum of all weights (including the new one).

The specific weight we use is $1/cos(θ)$, where $θ$ is the angle between the ray and the surface normal. To illustrate why we use this weight, consider the following diagram:

Here the red dot is the camera position, the dashed red line is the ray we’re using to sample geometry, and the black lines are the pieces of geometry we hit. The dotted blue lines are some angle around our ray.

As you can see from the diagram, the surface area within the angle around the ray for each piece of geometry is proportional to two things; the distance of the geometry from the camera position, and the angle of the geometry with respect to the ray. As the blue angle around the ray goes towards zero, the surface area for each sample becomes proportional to $d^2/cos(θ)$.

If we wanted perfectly uniform sampling in world space, then we could use $d^2/cos(θ)$ as our weight. However, if we use $1/cos(θ)$ as our weight instead, then we bias the sampling to the tune of $1/d^2$, which is desirable for the reasons described above.

Once caveat of this approach to geometry sampling is that triangles which are close to collinear with the camera position (ie have a very tight angle to the camera) have a low probability of being sampled. Using $1/cos(θ)$ as the weight makes it very likely that these triangles will be sampled if they’re hit by a ray, but the probability of them being hit could be very low. This could present itself as noise on light reflected from these surfaces. To counteract this, we can randomly displace the origin of the geometry sampling rays around the camera location. This doesn’t introduce bias, but should help reduce this noise.

For each ray, we store details about the chosen geometry sample in a G buffer, including the sum of weights, which are used to generate the virtual light.

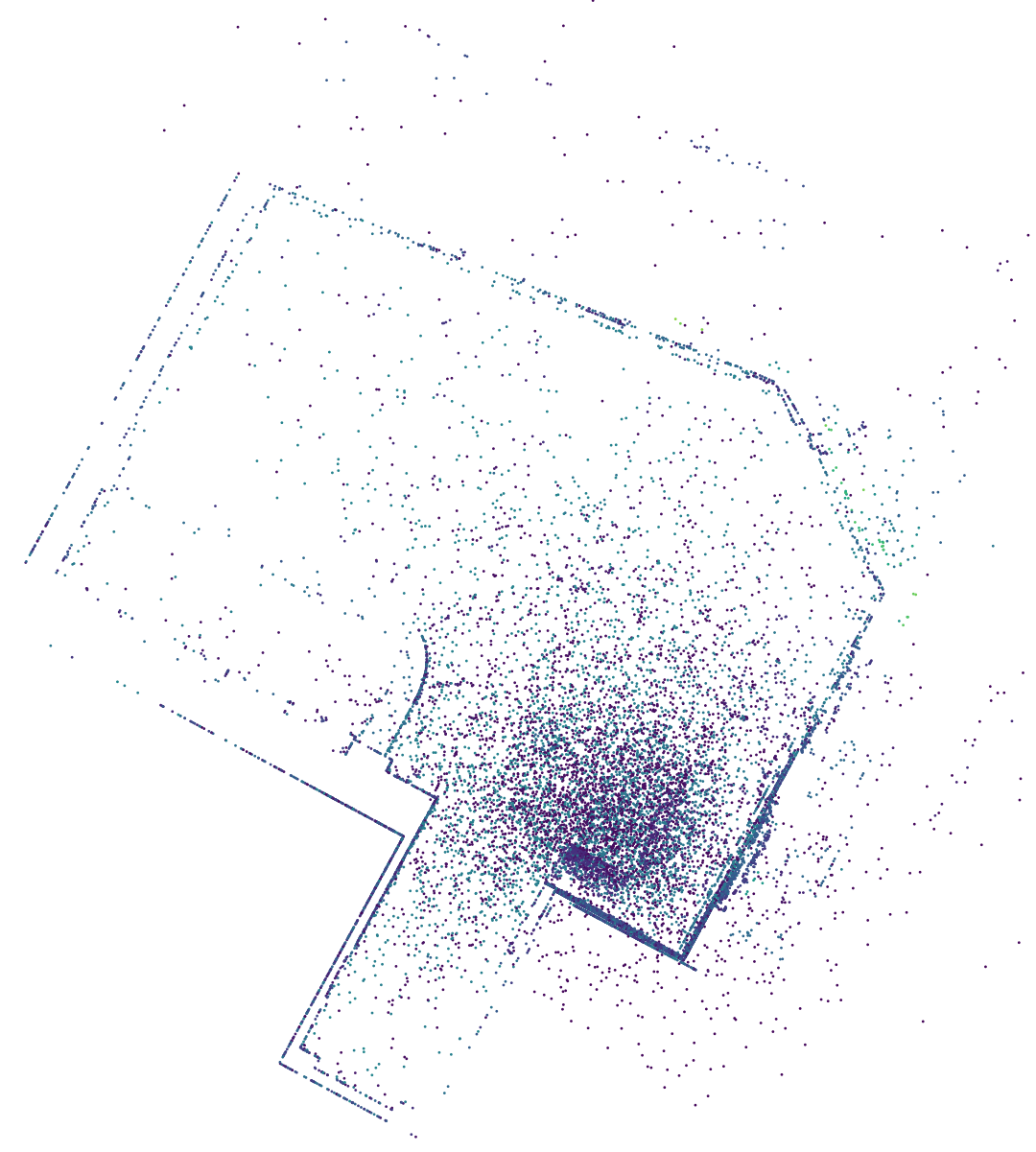

To illustrate the sampling pattern with a real-world use case, the following diagram shows a point cloud, from the top-down perspective, of points generated by my implementation in the sample scene. The colour of each point represents its height.

A total of 16,384 samples were used to generate this point cloud, and we can see a large number of samples around the location of the camera, reducing in density further away.

Creating Virtual Lights

We then perform a separate pass to calculate the lighting for each of these geometry samples. This is based on the ReSTIR DI light sampling, and generates initial samples in largely the same way as ReSTIR DI does. Resampling can be performed here, and this will be discussed in more detail later, but for the purposes of my example code one resampling technique is used, called screen space resampling, which re-uses reservoirs from ReSTIR DI for any geometry samples which are visible on screen. Ray traced visibility testing is then used on the chosen sample.

Once a source light sample is chosen, diffuse lighting is calculated from that source light to the geometry sample, and a virtual light is created at that point to represent the diffuse reflected light. Although you could represent these as point lights, for my example code I’ve used disk lights, as it reduces noise, as we can increase the radius in proportion to the distance from the camera, which corrects for the $1/d^2$ bias introduced by the radial sampling.

The radiance of the virtual light $R$ is scaled according to the sampling density $D$ and the sum of the weights $W_s$ for the ray used to generate that sample:

\[R \propto {\frac {W_s K} D}\]An additional scaling factor $K$ is required. This could be calculated from the total geometry surface area in the scene, or tuned manually for artistic effect.

Unless instant response to lighting changes is required, each virtual light created would usually have a lifespan of multiple frames before being replaced. So, for example if the lifespan is 10 frames, only 10% of virtual lights would be replaced with newly sampled lights each frame. This increases performance, as fewer new virtual lights need to be generated each frame, at the expense of slower response to lighting changes. As will be discussed in more detail later, a longer lifespan also allows ReSTIR DI’s temporal resampling to be more effective.

When lighting pixels using virtual lights, one concern is weak singularities. These are bright spots very close to virtual lights, where the small distance between the light and surface results in a very large geometry term. To reduce this issue, when calculating the contribution of a virtual light to a pixel, we clamp the distance at some lower bound, which in turn results in a upper bound for the geometry term, limiting the brightness.

This clamping introduces bias to the image, which in my current implementation is uncompensated. Existing solutions I’ve seen for compensating for this bias involve tracing additional rays, which would have a potentially significant performance impact, so it’s been left uncompensated, but it may be worth looking into cheaper compensation approaches. As the number of virtual lights increase, the clamping distance can be reduced, which will reduce the bias.

Implementation and Results

For my example implementation, I’ve built on a fork of Nvidia’s RTXDI, which you can find on github here. This saved me from having to reimplement ReSTIR from scratch, and also allows me to perform direct comparisons to ReSTIR GI, which is also included in RTXDI.

All code was run on a system with a desktop RTX 3070 GPU, and was run at 1080p, with the default settings in the RTXDI sample app. This includes NRD denoising, and DLSS (with both input and output resolutions of 1080p). The following GSGI examples are using 16,384 samples per frame, with a virtual light lifespan of 30 frames, resulting in just under 500k virtual lights being used. ReSTIR GI uses the default RTXDI settings.

First, we’ll look at the arch example from above, which represents a relatively simple global illumination scenario, with the sun as the dominant light source:

As we can see, GSGI achieves its goal of being significantly faster than ReSTIR GI. The base frametime without GI was 18.3ms (55fps), which became 32.7ms (31fps) with ReSTIR GI, or 19.1ms (53fps) with GSGI. As such, ReSTIR GI costs approximately 14.3ms per frame, while GSGI costs about 0.8ms. Of this, around 0.3ms are the actual GSGI passes, with the remainder being the impact of the virtual lights on the rest of the rendering process.

We can also see GSGI produces global illumination broadly in line with what we would expect, and with ReSTIR GI. Sunlight bouncing off the floor and wall of the arch illuminate the ceiling and walls, and we can see specular reflections of the sunlight on the wall to the left of the image, and the ground below it.

However, the quality of GSGI does not match that of ReSTIR GI. Although not obvious in these still screenshots, there is some noise and boiling when using GSGI, particularly on specular and metallic surfaces.

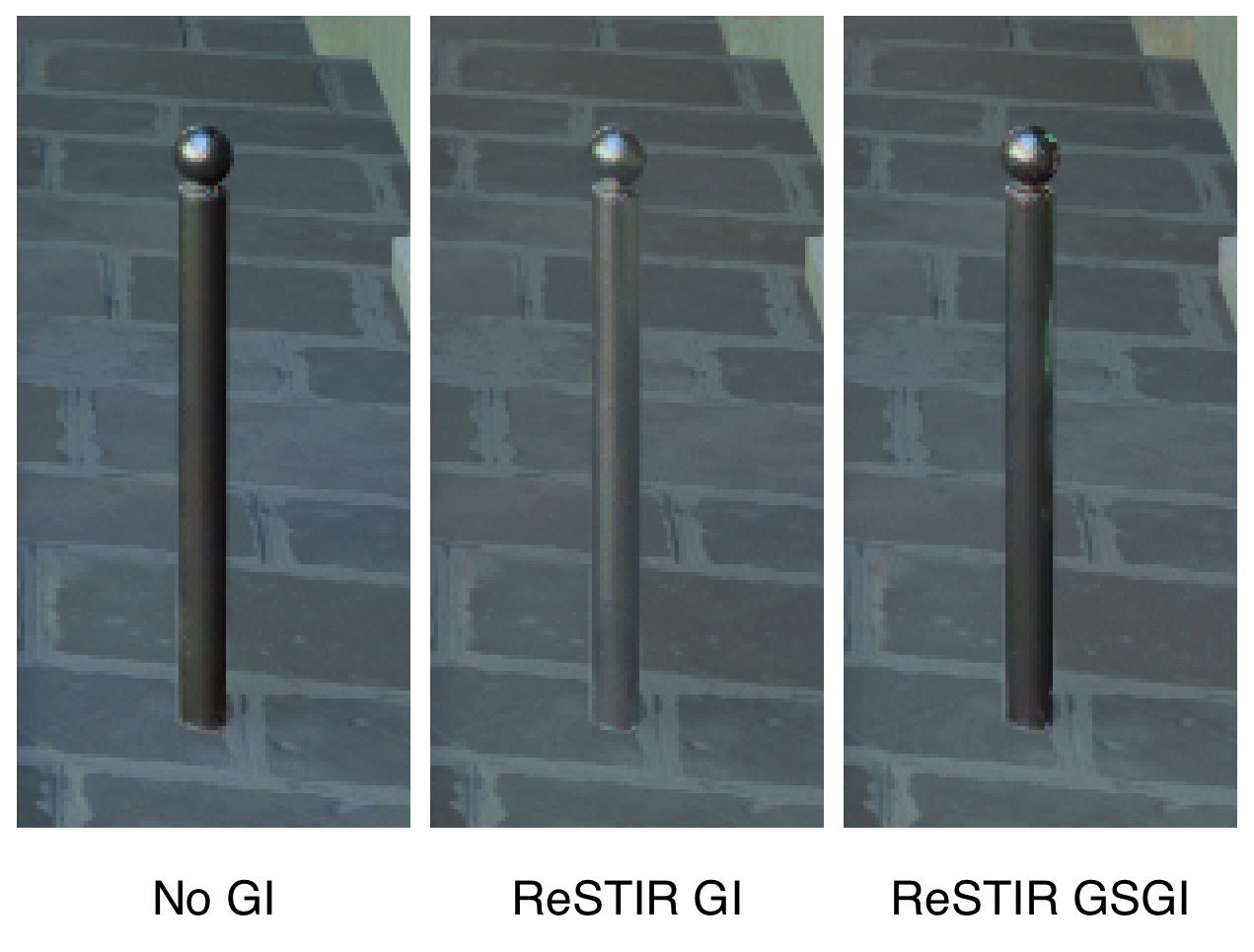

Let’s take a closer look at the metal pole in the lower right of the image:

We can see that, while ReSTIR GI produces high quality metallic reflections, GSGI struggles here. There is noise visible on the right hand side of the pole, and the top right, and this is quite noticeable in motion. Other specular and metallic surfaces, particularly those with fine detail, also show similar noise.

Specular Issues

To illustrate these issues with specular and metallic reflections, we’ll take a look at an indoor scene with more complex lighting.

Here we can see that GSGI illuminates the ceiling at the back with light bounced off the floor and walls. We can also see the metal drinks cart on the left largely matches the ReSTIR GI image, and the ice bucket on the right includes some metallic reflections, although not as accurately as ReSTIR GI.

However, the lampshade at the top of the image has noise, which is particularly noticeable in motion, along with boiling on both the drinks cart and the ice bucket. There is also occasional boiling on other specular surfaces, not seen in this image.

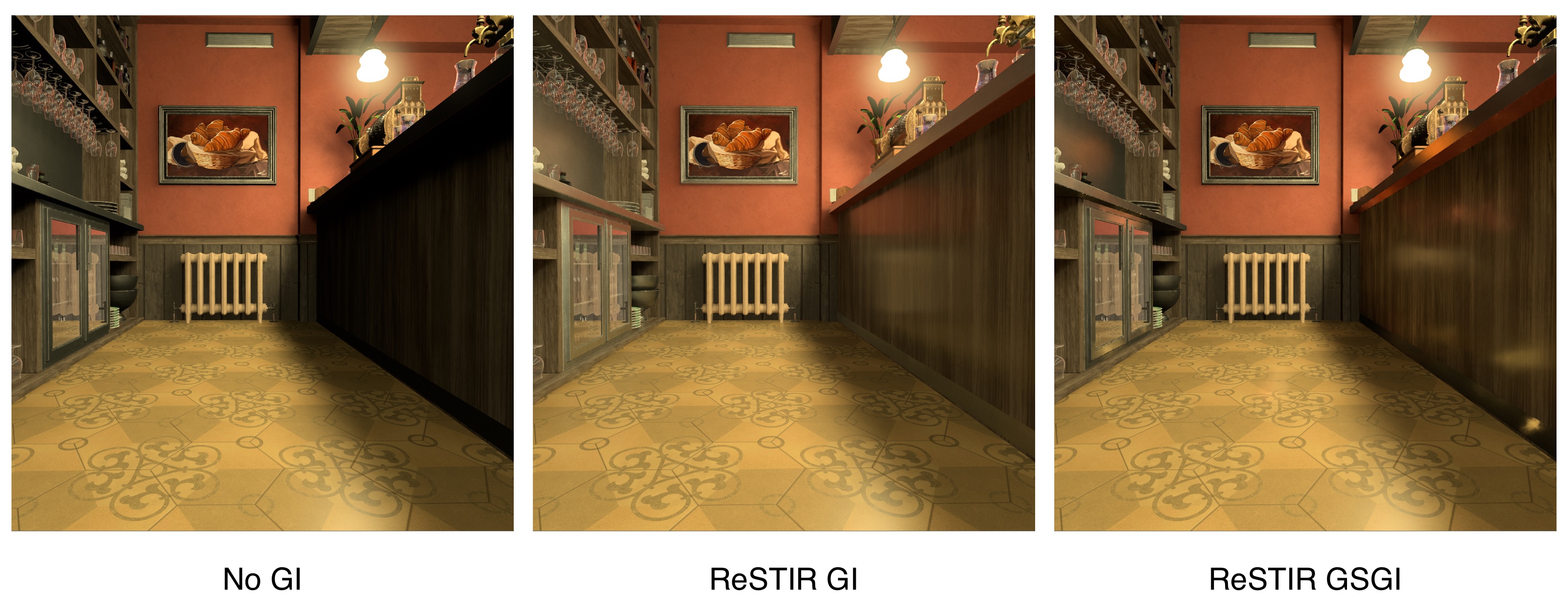

For a more extreme example, let’s look at this image from behind the counter:

We can see that ReSTIR GI produces high quality specular reflections on the right of the image, with the wall, radiator and floor clearly visible reflected underneath the counter. The metal surfaces on the left of the image also produce accurate reflections.

GSGI, however, suffers from significant boiling here, both on the counter to the right and the metallic surfaces on the left.

Causes of Noise and Boiling

There are two main causes of the noise and boiling we see, particularly noticeable on specular and metallic surfaces. The first of these issues is how GSGI interacts with ReSTIR’s temporal resampling, and the second is related to the way in which initial samples are generated.

One important note to make here is that these issues aren’t significantly impacted by the number of virtual lights. Although a very low number of virtual lights would cause its own issues, increasing the number of virtual lights beyond the amount used in this example doesn’t have a meaningful impact on quality.

Interaction with Temporal Resampling

As mentioned in the intro to ReSTIR DI above, the algorithm involves two resampling steps, temporal and spatial. Temporal resampling takes information from the same pixel in previous frames, which effectively means that if a pixel finds a good sample in one frame, it can be reused across subsequent frames.

In normal usage, we would expect lights being used for ReSTIR to be long lived, only turning on or off very infrequently. As such, a light used to shade a pixel in a previous frame is almost certainly going to be avilable to shade the same pixel in subsequent frames.

When using virtual lights, though, that isn’t the case. Virtual lights are created and destroyed very quickly, and if a pixel is sampling a virtual light in one frame which isn’t there in the next, then ReSTIR can no longer rely on temporal resampling for that pixel.

The lifespan of the virtual lights has a significant impact on this. With a very short lifespan, say 4 frames, that would mean 25% of virtual light samples are invalidated every frame. This results in very noticeable noise across the image as ReSTIR can no longer rely on temporal resampling for stability.

This is why a lifespan of 30 frames was used in the examples. The default maximum duration of temporal samples used by ReSTIR in the example was 20 frames, so using a virtual light lifespan higher than this allows us to achieve relatively low noise from invalidated temporal samples. The noise could be reduced further by using an even longer lifespan, but that would negatively impact how quickly global illumination can respond to lighting changes.

Directionality of Initial Light Samples

ReSTIR DI supports a variety of methods of choosing the initial light samples for each pixel. For the examples above, I have used a technique called ReGIR, which divides the scene into cells and presamples a large number of lights for each cell, with each pixel then sampling from the pool of presampled lights ReGIR prepared for the cell it’s in.

ReGIR, along with the alternative presampling options, doesn’t care about what direction these light sources are coming from, and just considers general illumination over the volume of the cell. This is no problem for diffuse lighting, as if you have a pool of presampled lights, then for any given surface you will need only a handful of samples before you’re likely to find one which contributes meaningfully to the diffuse lighting of that surface.

For specular lighting, though, the directionality of the light source is important. With a relatively low number of relatively bright light sources (eg the direct light sources in a scene), this isn’t a big problem, as there’s still a pretty high likelihood that the light will be sampled at least once in the neighbouring region of pixels used for spatial resampling, and will be retained when found with temporal resampling.

GSGI relies on a very large number of relatively dim virtual light sources, though. For specular lighting it means that the probability of sampling one of the very small number of virtual lights which happens to provide meaningful specular illumination to a given pixel can become very low.

This results in the boiling we see on specular surfaces. One pixel will, by chance, find a virtual light sample which provides meaningful specular illumination, and spatial resampling will cause neighbouring pixels to reuse the same sample. Then, after the light becomes invalidated, the pixels will have to choose new samples which are unlikely to provide similar specular illumination.

Solutions for Noise and Boiling

Ignore Specular Lighting from Virtual Lights

One straightforward solution is, when calculating the lighting of a pixel from a virtual light source, to simply ignore the specular component of the lighting. This maintains the diffuse indirect illumination, while eliminating most of the noise and boiling, as they are most prominent in the specular component.

Here are some examples with both diffuse and specular lighting from virtual light sources on the left, and diffuse only on the right:

We can see that, without including the specular component from virtual light sources, we still get indirect illumination lighting the ceiling in the first comparison, and the counter in the second comparison. We also don’t see the noise or boiling present in either of the two examples.

There is still some slight noise present in motion which isn’t visible here, however I feel that could be eliminated with sufficient tweaking of settings.

The loss, of course, are the kind of specular reflections we saw with ReSTIR GI. As GSGI is over an order of magnitude faster, this may be a worthwhile trade off, and another technique could be used for these reflections while still achieving higher performance than ReSTIR GI.

Directional Initial Sampling

One possible solution is to consider the direction of lights when performing initial sampling. I implemented a directional variant of ReGIR, which considers the direction of light sources when presampling, and then chooses initial samples for each pixel based on directions generated by the surface BRDF.

This produced interesting results, but wasn’t sufficient to solve the problem for GSGI. I’ll write up another article in the future explaining how my directional ReGIR variant works and why it isn’t quite the right solution here.

Remapping Expired Virtual Lights

As expired virtual lights cause the loss of data which could be used for temporal resampling, it would be tempting to attempt to map expired virtual lights to newly created ones. With a sufficiently large number of virtual lights, it’s highly likely that there will be a new light which is close to the expired light and has similar direction and radiance. If we could map expired virtual lights to new virtual lights, this could improve temporal stability.

Actually performing this mapping would be non-trivial, though. The virtual lights aren’t organised in a data structure which would allow us to efficiently find similar lights, so such a data structure would need to be generated each frame. There’s also a risk of artifacts due to differences between the expired virtual lights and the new ones replacing them.

Disable Temporal Resampling

As some of the noise and boiling issues are related to how GSGI interacts with ReSTIR’s temporal resampling, a valid option is to simply disable temporal resampling and restrict ReSTIR to spatial resampling only. The major negative here is performance. With only spatial resampling, ReSTIR typically needs more samples, and more spatial resampling, to produce similar image quality as it can with both spatial and temporal resampling.

This could be a worthwhile option for situations where very fast response to lighting changes is required. Short virtual light lifecycles aren’t really viable with temporal resampling, as discussed above, but while only using spatial resampling they could be reduced as low as required, with no impact on image quality.

The trade off for this would be performance, both due to the additional cost needed to get good results out of ReSTIR without temporal resampling, but also due to the need to generate more virtual lights per frame, to ensure a good number of total virtual lights.

Optimisations

While working on the implementation, several potential optimisations came up, which I haven’t yet implemented as performance was already pretty good while I worked on image quality issues. I’ll note them here, though, as there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit.

Geometry Sampling Directions

When performing radial geometry sampling, my code simply sends rays in completely uniform random directions from the position of the camera. A much better solution would likely sample in a non-uniform manner, though.

Firstly, it would be sensible to increase sampling density in the direction the camera is facing, as the effect of fine-grained global illumination will obviously be more visible there.

Secondly, it would make sense to dynamically adjust sampling density based on the amount of geometry in a given direction. For example, the unit sphere could be segmented into some number of partitions, and for each partition an estimate could be made of the amount of geometry in that direction based on the $W_s$ values from the previous frame. The sampling density for each partition would then be proportional to that estimate.

The benefit of this is most evident when looking at the area around the camera in the point cloud image above. A very small patch of floor beneath the camera contains thousands of samples, which is obviously overkill.

Resampling During Virtual Light Creation

As discussed above, while sampling source lights to generate virtual lights, there’s a possibility of including resampling. I added screen space resampling, which resamples from reservoirs which are on screen and used for ReSTIR DI, but this has minimal impact on quality.

In the example scene, typically somewhere around 80% of virtual lights end up failing visibility checks against their chosen light source. That is, the virtual lights are dark because the light source picked during initial sampling is shadowed. With ReSTIR DI you would get similar figures without any resampling, but spatial and temporal resampling significantly increasing the number of pixels with non-occluded light samples.

Resampling is more difficult with virtual light samples, though. Spatial resampling could be possible, but it would require geometry samples to be stored in a data structure such that they could quickly find nearby samples, and even then would likely be far less effective than spatial resampling in ReSTIR DI, as the spatial samples will be much less similar on average.

Temporal resampling would be similarly challenging, as there would not necessarily be a sufficiently similar geometry sample from a previous frame.

Async Compute

The example code runs each GSGI pass standalone, however due to the relatively low number of threads, hardware utilisation isn’t particularly high. Running the GSGI passes asynchronously alongside other passes should increase hardware utilisation and improve performance.

Future Work

I’ve already implemented a simple follow-up algorithm to this, called ReSTIR PMGI, or Photon Mapping Global Illumination, and you can probably guess how it works from the name. I’ll write an article on it shortly.

Following on from that, I feel that adopting something like a radiance cache approach may be worthwhile. One of the things I’ve learnt from implementing GSGI is that the constantly changing virtual lights make it much harder to achieve temporal stability, particularly with ReSTIR’s temporal resampling depending on stable light sources.

A radiance cache approach could solve those issues by providing a consistent reference point for indirect lighting. Each surface or element in a radiance cache could be treated as a virtual light and fed into ReSTIR DI, but unlike in GSGI, temporal samples would never need to be invalidated, as it should always be possible to create a 1:1 mapping of a point on the radiance cache in one frame to the same point on the cache in the next frame.

A radiance cache would also help solve the problem of directionality of initial samples, as they are typically built in such a way that they can be easily sampled with BRDF sampling. Those samples could then be fed into ReSTIR DI as initial samples, ensuring high quality specular reflections.

Given the widespread use of radiance caches for GI, along with the popularity of ReSTIR, it wouldn’t surprise me if other people have already combined them, but it still seems like a worthwhile project to attempt.

Closing Comments

Aside from some simple tutorials, this has been my first time ever working on graphics code, so although it’s not perfect, it’s been satisfying to come up with my own approach to a problem, get it implemented, and come out of it with results that at least vaguely resemble what I was hoping for.

As I’m only learning the field, there’s a good chance that I’ve left plenty of bugs and optimisation opportunities in the code, and any fixes or suggestions would be appreciated.