ReSTIR PMGI - Even Faster Ray Traced GI with Virtual Lights

In my post on ReSTIR Geometry Sampling Global Illumination, or GSGI, I wrote about how virtual lights can provide a high performance ray traced global illumination solution when combined with ReSTIR’s direct illumination algorithm. In this post, I’m going to discuss ReSTIR Photon Mapping Global Illumination, or PMGI, which uses photon mapping to create the virtual lights. It’s a faster solution than GSGI, although perhaps less well suited to large open areas.

ReSTIR and Virtual Lights

I’d recommend that you read my post on GSGI for a more in-depth discussion on this, but here’s a brief intro on ReSTIR, and why virtual lights are a compelling approach to global illumination when combined with ReSTIR.

ReSTIR is a ray traced direct illumination algorithm, which has the benefit of being able to handle a very large number of light sources with minimal performance penalty. If we can represent the indirect illumination being reflected off surfaces as virtual lights, then we can feed these into ReSTIR, and calculate both direct and indirect illumination in a single pass. Because ReSTIR can handle such a large number of light sources, we can use hundreds of thousands, or even millions of virtual lights to represent indirect illumination, and still achieve high levels of performance.

GSGI creates virtual lights by randomly sampling the geometry in the scene and determining the indirect illumination being reflected off each, while PMGI creates virtual lights by mapping photons from light sources.

Photon Mapping Global Illumination

Photon mapping is a long-studied technique in rendering, which consists of tracing rays from light sources, to find surfaces they illuminate. This mirrors the physical behaviour of photons being emitted from those light sources, hence the term photon mapping.

My approach to photon mapping is very simple. We randomly sample light sources in the scene, and then trace rays from those light sources, creating a virtual light at the point each one hits a piece of geometry, representing the diffuse indirect illumination reflecting from that point. Those virtual lights are then fed into ReSTIR DI, which calculates both direct and indirect illumination in a single pass.

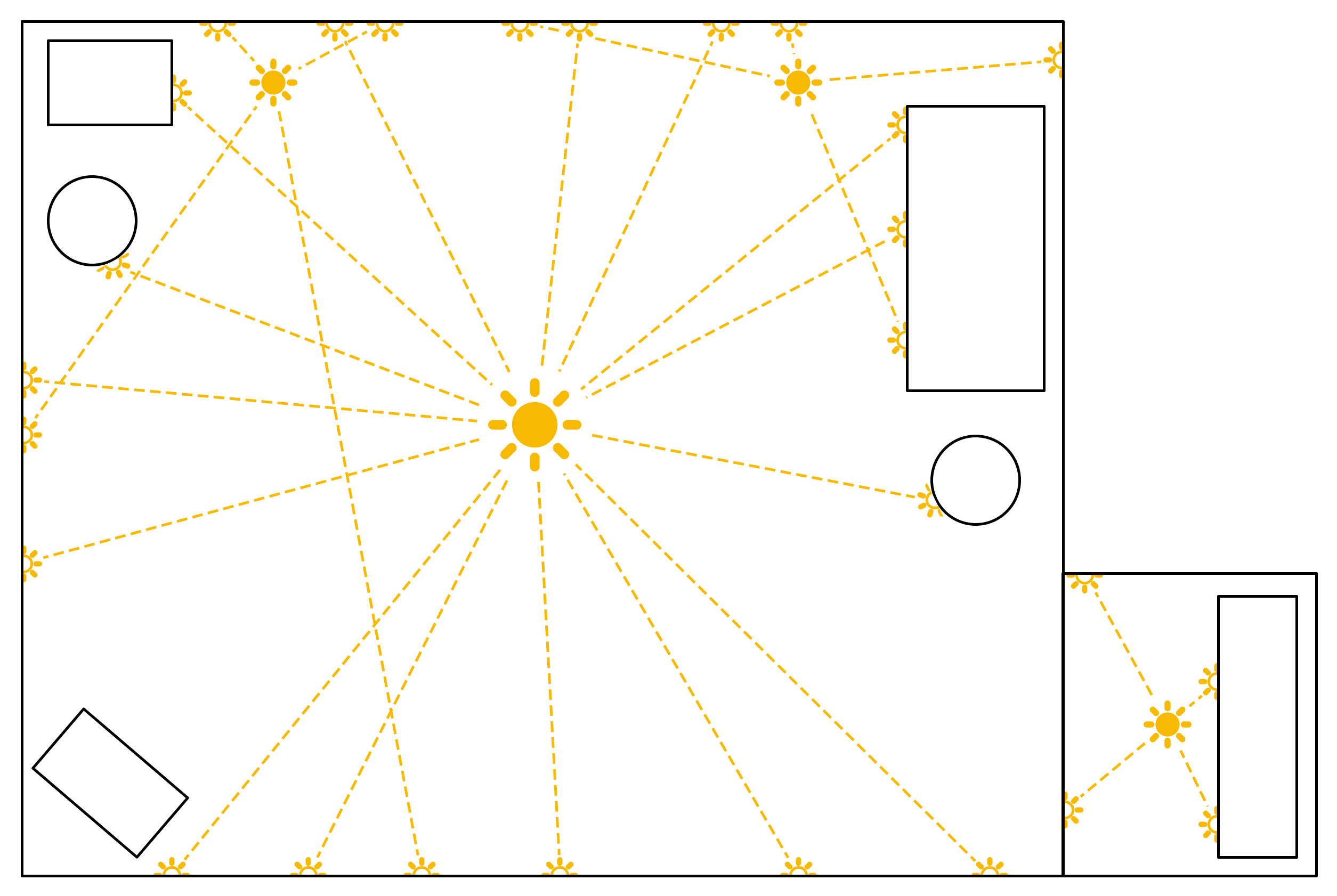

This diagram shows a simplified 2D representation of PMGI. Each of the filled orange sun symbols represents a light source, and the dashed lines from these represent rays traced from those lights. At each ray’s closest hit location, a virtual light is created, shown as a hollow half-sun.

Lights are sampled proportional to radiance, so we can see a bright central light source emit more photons than the other, less bright light sources. Because we sample light sources by radiance, each virtual light has the same radiance, subject to the diffuse albedo of the surface.

The virtual light sources are also sampled when performing photon mapping in subsequent frames. As such, although in each frame only a single bounce of indirect lighting is calculated with each photon mapped, over multiple frames more complex multi-bounce lighting can be represented, in theory representing infinite bounces.

In the form I’ve implemented, PMGI doesn’t distinguish between near or far light sources, and generates photons only based on the radiance of the light. This makes it poorly suited to large open spaces, as a very large number of photon traces may be needed to handle both near and far lights. A future improvement would be to weight light sources by distance to the camera, making it more suitable for large environments.

Implementation

My implementation of PMGI was built on a fork of Nvidia’s RTXDI repo which you can find here. It has a lot of shared code with my GSGI implementation, which can be found in the same repo.

The implementation of PMGI is similarly simple, requiring only a single ray tracing pass. Source lights are sampled proportional to radiance, so when creating the virtual lights we use a constant brightness, attenuated by the diffuse albedo of the surface.

My current implementation supports local lights including a variety of different area light sources, although doesn’t currently support infinite lights (like the sun) or light from an environment map. Both of these could be added, but it would require a bit more work to efficiently sample them. Shaped spot lights aren’t supported either, as there are none in the scene, but again they could be added.

Like with GSGI, I retain virtual lights over a number of frames, to improve performance and achieve better results with ReSTIR’s temporal resampling.

I’ve also implemented configurable distance clamping when calculating lighting from virtual lights to prevent weak singularities, which introduces some bias. For further explanation, see my GSGI post.

One benefit of this PMGI implementation compared to my GSGI implementation is that we get a far higher proportion of usable virtual lights. As discussed in the GSGI post, a large proportion of geometry samples don’t result in usable virtual lights, as the source light is occluded. Depending on the scene, only around 20% of the geometry samples may end up yielding usable virtual lights.

With PMGI, however, every photon which hits a surface creates a virtual light, so we have 94% of photons resulting in usable virtual lights in the sample scene.

Here’s a point cloud showing the location of virtual lights generated by my PMGI code in the sample scene, from a top down perspective:

Comparing to the point cloud in the GSGI post, we no longer have points centred around the camera, instead we get more uniform distribution of virtual lights around the scene. We see clusters of virtual lights near light sources, with particularly tight clustering on lampshades (the circles near the walls).

Results

All my testing has been run at 1080p on a desktop RTX 3070 graphics card, using default settings within the RTXDI sample app, including denoising. GSGI has been configured with 16,384 geometry samples per frame and a 30 frame virtual light lifespan (the same as in my GSGI post) and PMGI has been configured with 8,192 photons mapped per frame and a 30 frame lifespan, resulting in around 250K virtual lights.

Let’s take another look at the comparison image from the top of the post:

The average frame times during testing of each technique were as follows:

- ReSTIR DI (without GI) - 18.335ms

- ReSTIR GI - 32.205ms

- ReSTIR GSGI - 19.131ms

- ReSTIR PMGI - 18.730ms

We get a cost of 13.9ms for ReSTIR GI, 0.8ms for GSGI, and just 0.4ms for PMGI. When using PMGI, the photon mapping pass takes just 0.16ms, with the remainder being the impact the larger number of light sources has on other passes.

The example images above are only including diffuse lighting for virtual lights with GSGI and PMGI. As PMGI also relies on a large number of virtual lights, it suffers from the same noise and boiling issues with specular reflections of virtual light sources. I won’t go through them again here, but the results are largely similar to the examples shown in the GSGI post.

There is still some noise visible when using PMGI without specular lighting from virtual light sources, but as with GSGI, this could probably be reduced quite a bit by appropriate tweaking of denoising settings. As this noise is primarily caused by expiring temporal samples, it can also be reduced by increasing the virtual light lifespan, at the cost of slower response to lighting changes in the scene.

Like GSGI, PMGI requires a reasonably long virtual light lifespan (ie over 20 frames) to allow ReSTIR’s temporal resampling step to work well. Faster response to lighting changes could be achieved by reducing the virtual light lifespan and relying only on spatial resampling, at a performance cost due to the need for more samples to make up for the quality loss of dropping temporal resampling.

Future Work

One straightforward way to improve performance would be to run the photon mapping pass asynchronously alongside other passes. With 8,192 photons per frame in the example above, we’re creating only 256 warps in the pass, which is severely underutilising the RTX 3070, which has a maximum occupancy of over two thousand warps.

It’s also likely that good results could be achieved with far fewer total virtual lights, depending on the scene. I saw little to no performance benefit of dropping below 8,192 per frame in the sample scene, likely due to the GPU already being underutilised at that point, but if run concurrently with other passes, fewer virtual lights could reduce the performance impact even further.

As discussed above, my current implementation of PMGI isn’t well suited to large environments, as it will sample just as many photons from far away lights as nearby lights. However, it would be possible to weight the sampling algorithm based on distance to the camera. Infinite lights like the sun could also be sampled more densely in directions towards the camera, and less densely further away. In both cases the radiance of the virtual lights would then need to be adjusted to account for the sampling bias.

The potential solutions for noise and boiling discussed in the GSGI post would also apply here.

Closing Comments

This was a pretty quick project to implement, as I could leverage a lot of the work I had already done for GSGI, and it’s nice to get something from concept to working code so quickly, particularly as it works reasonably well.

Performance was a big positive here, as it’s running twice as quickly as GSGI, and I suspect that could be improved considerably by running the photon mapping pass asynchronously and reducing the number of virtual lights. Depending on the scene, I think it would be quite possible for PMGI to produce good results with as little as 0.1ms impact on frame times, if you’re already running ReSTIR DI. Not quite free, but as close as you’re going to get for a ray traced GI solution.

There’s still work to do to get the noise and boiling issues on specular reflections sorted, but even with only diffuse lighting being calculated from virtual lights it could be a good option given the extremely low performance cost.